Reverse Engineering a Game Data Archive

I don’t pretend to be any kind of expert in reverse engineering. As a coworker of mine said, “if I was, I’d be getting paid a lot more than I am right now.” But on a hobby level I’ve started taking a crack at it, and I wanted to type up some of what I’ve learned - mostly as an aid to help me understand it and remember it myself.

There’s an old MS-DOS game that I really enjoyed as a kid, and I thought it would be fun to poke around in it and see if I could extract some assets or otherwise make some progress toward some mods, documentation, or a tooling suite.

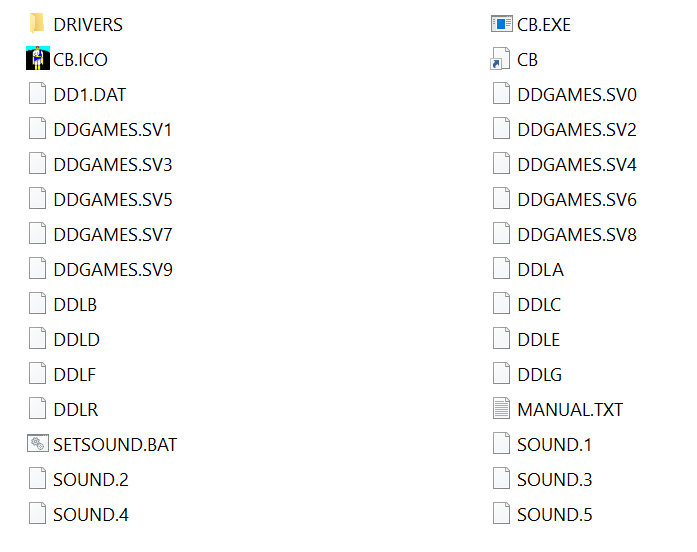

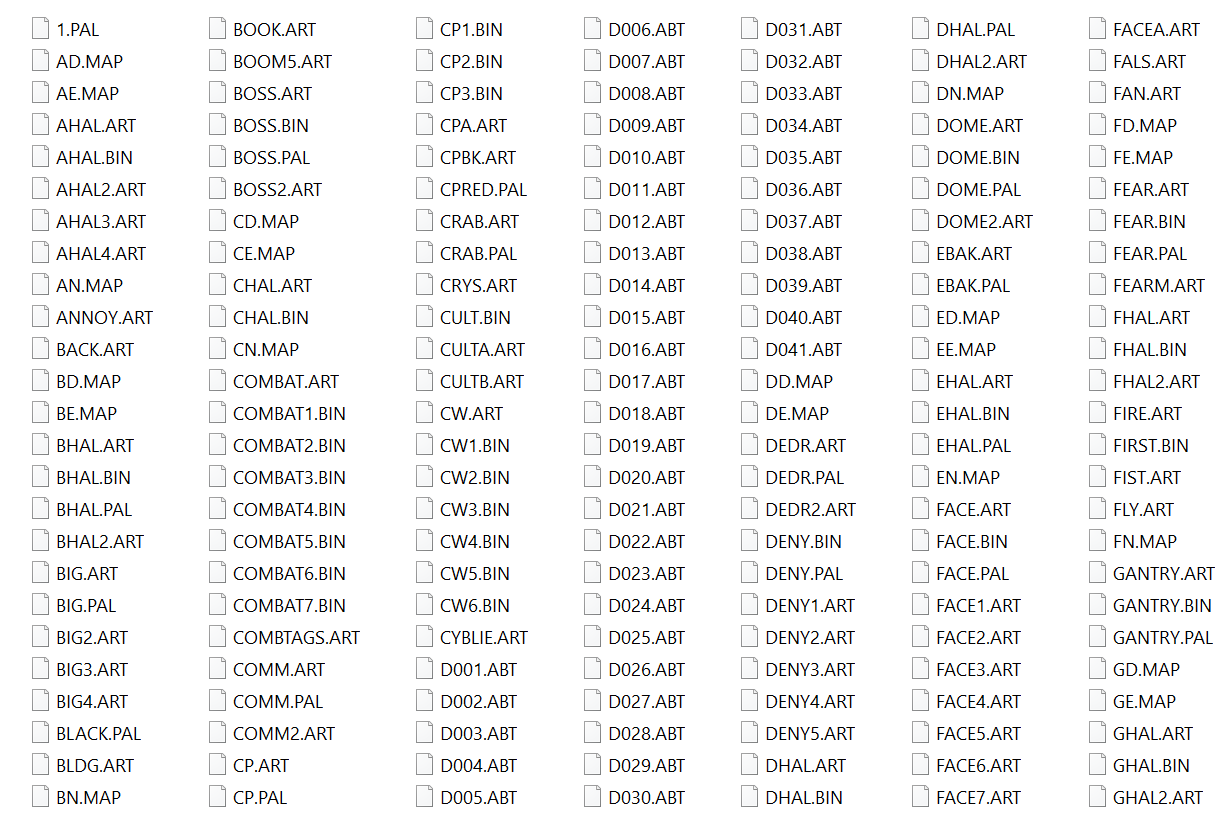

When you open up the game files you see this:

Aside from the manual.txt file, this is all binary data not intended for human consumption. Which means that if we want to understand what these files are, we need to look at them in the way a machine looks at them. You need a hex editor; I like HxD.

Now when you open up a binary data file in an editor like HxD, it basically shows you the binary data on the left-hand side (but in bytes instead of bits, using hexadecimal form, for a variety of reasons) as well as a translation on the right-hand side.

I said these files weren’t intended for human consumption, but that doesn’t mean that a human can’t learn something from them.

Strings, for example, are ultimately expressed as bytes, so if the data files have strings in them then those will jump out in our hex editor as snippets of clear text. Mixed in with those easily-readable strings will be garbled characters representing non-string data. But we can often use those, too, as you’ll find out.

Let’s look at the files with HxD and see what we’re dealing with.

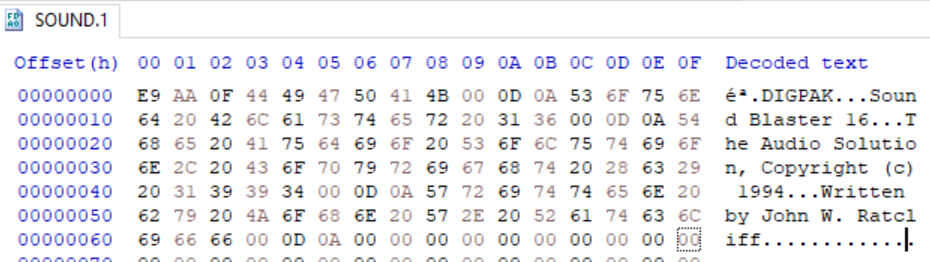

SOUND.*

We see a lot of stuff about SoundBlaster drivers, so these are probably what they say on the tin: audio drivers. Not too interesting. Let’s keep looking around.

DDGAMES.SV*

I won’t show the internals because there’s nothing human-readable, but from the file extension and knowing the features of the game (saving your progress in up to 10 slots) I can guess that they are save game files. Let’s keep going.

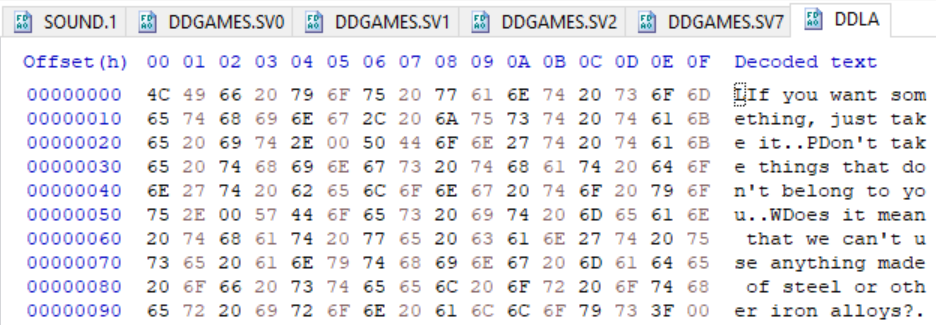

DDL*

These are almost entirely human-readable! And again, knowing the game, I recognize the text as NPC dialogue strings. So these are a kind of game asset file containing string resources for conversations and interactions. DDL means something like “Data DiaLog”? Not sure.

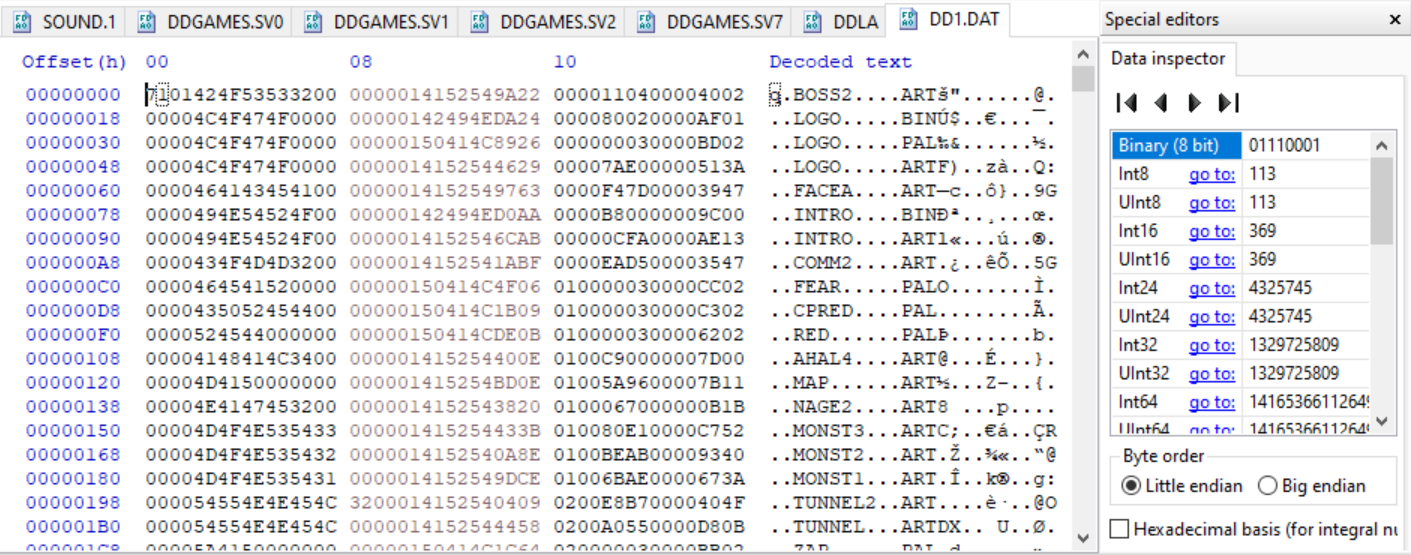

DD1.DAT

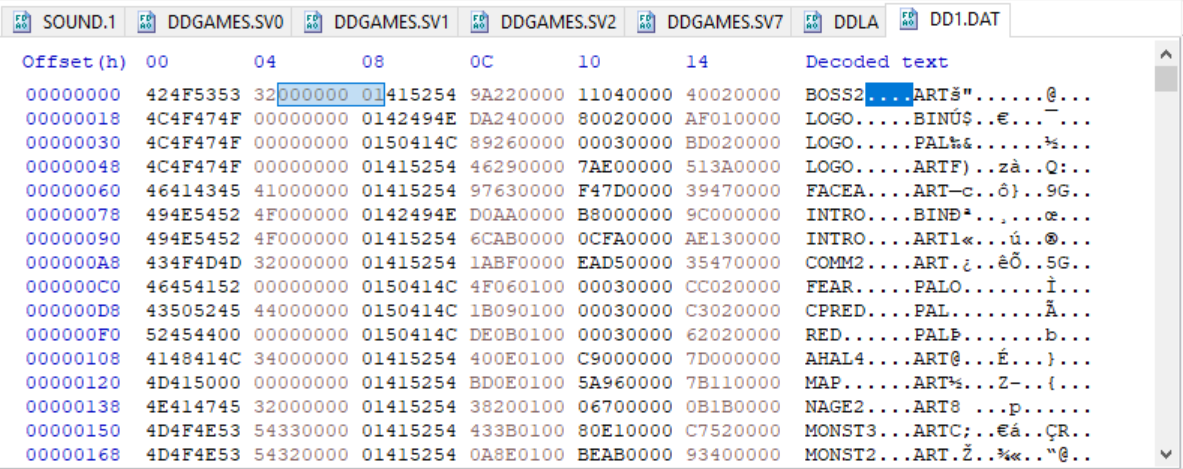

Now right away you know that this is an important file. It’s 1.8MB, an order of magnitude bigger than any other file in the directory. And when we look at it in our editor we see some intriguing strings:

Asset file names! BOSS2.ART, MONST2.ART, etc. This is all the game’s art, music, and other assets bundled together into a big blob of data. But as I said above, there are a bunch of weird symbols (non-string bytes) mixed in with the filenames. So what does it all mean?

Well if you look around online, the first thing you’ll be told to look for is the “file magic”, or magic bytes. This is a signature that can identify the file to machines, like a file extension but unchangeable. If we rename DD1.DAT to DD1.TXT, a sequence of bytes at the beginning of the file will remain unchanged and continue to identify the file type to machines.

So looking at this file, we might be tempted to think that the first two bytes before our first filename, “BOSS2”, are the magic bytes. In this case, 0x71 0x01 or q.

In reality there’s no iron law that says a file has to have magic bytes. In fact, magic bytes are quite common in files that don’t know what application will use them but are not really necessary in custom files intended to be used by a single application. As an example, a zip file can be used by a ton of different archiving applications. So it’s a good idea for a zip file to identify itself (in addition to a file extension) with the magic bytes PK.

But in our case, this is a custom data archive intended to be used with a single application - the main executable, CB.EXE. So there’s no need for magic bytes. The CB.EXE application knows what DD1.DAT is and how to use it.

Instead, this 0x71 0x01 sequence is telling us the number of files in the archive: 369. It actually tells us something else as well, which is that the data archive is encoded using little endian byte order.

To expand a bit, the 0x71 0x01 byte sequence can be read as characters (q.) or as a number. And it can be read as a number in two different ways, either 369 or 28,929. Which number you get depends on which Endianness technique you use.

Now there are other ways you can find out what the Endianness of this file is, but all of them are basically the same thing: you take some sequence of bytes in the file that seems like a number, you keep both the Big and Little Endian value in mind, and you puzzle your way through the file long enough to eliminate one of the two options.

In this case, a manual count reveals there are 369 filename strings in the file so we can be pretty confident that this opening sequence is telling us that. It’s also just a logical thing to put at the top of the file.

So in our hex editor let’s just delete the first two bytes to make it easier to reason about the rest.

I modified the view to group the bytes into sets of four, to make it easier to understand what’s going on.

The first two sets of four bytes (the first eight bytes) are the filename. A lot of these have empty sequences of 0x00 bytes because not all the filenames need to take the whole space. But for consistency, all the filenames use eight bytes to allow room for the longest ones.

The next four bytes are the file extension, a 0x01 flag byte followed by a three-character extension type like ART or PAL (for palette).

After that things get less clear. We have twelve bytes to go until the next filename starts, and we don’t really know what these numbers mean or even how many there are. It could be any combination of two, four, and six-byte numbers that fit into a twelve-byte space.

However, we know that generally a file definition like this is going to contain a couple things:

- file name

- file extension

- pointer/offset (where in the data after the list of filenames the data for this file begins)

- size/length (how far to go from the pointer to get all the data for this file)

- decompressed size (if the data in this file is compressed, how big the file should be once it’s uncompressed)

We’ve found two of these, the file name and extension. Probably the remaining twelve bytes contain the offset, length, and decompressed size in some order.

This is where I just did some experimenting and reasoning. If you assume that the second or third number is the offset, you find out pretty quickly by jumping around using your hex editor that you get offsets that are so large they point to some place beyond the end of the file. So the second and third values can’t be offset, which means it must be the first.

And for the other two sets of four bytes - which is length and which is decompressed size? Well, that’s pretty easy. If we assume the second sequence is length then we end up with more bytes than are in the entire data archive! So the second must be decompressed, and the third must be length.

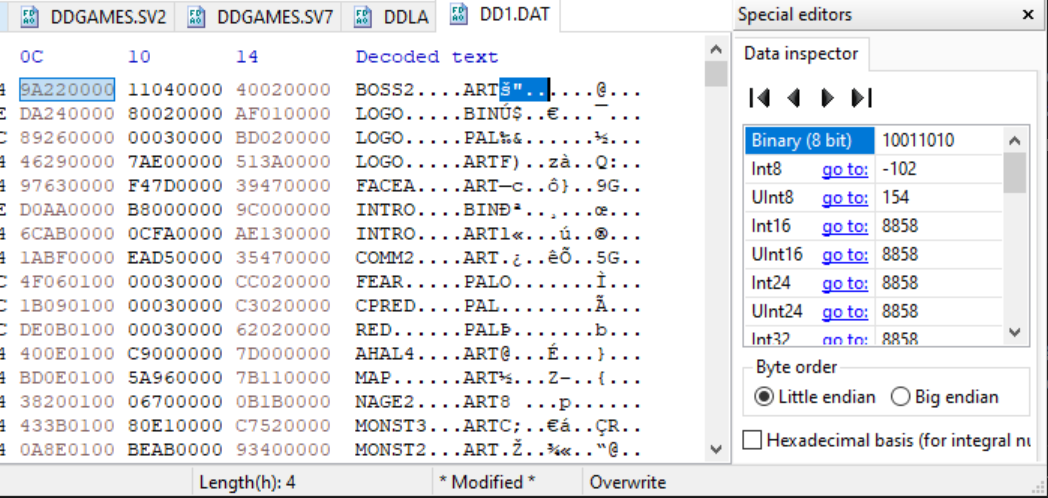

Let’s check the numbers given what we believe to be true, remembering to look at the Little Endian version instead of the Big Endian.

The first four bytes are offset:

This is how far down to jump in the file to get the to the data for BOSS2.ART.

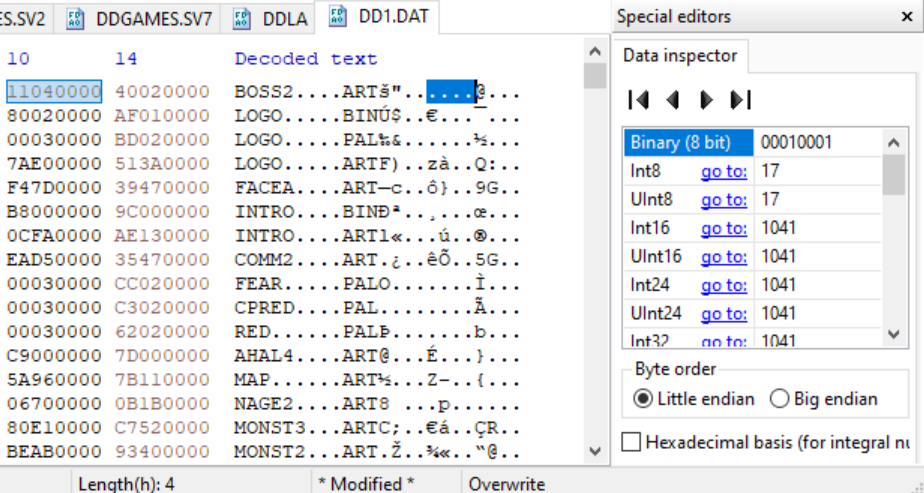

Up next is the number of bytes the file should be after decompression:

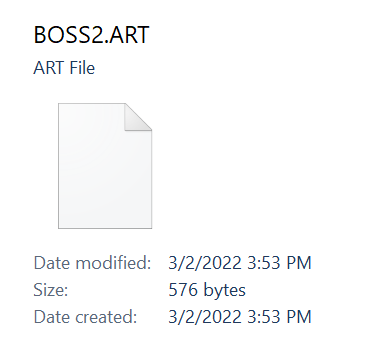

So we should expect BOSS2.ART to be 1041 bytes uncompressed.

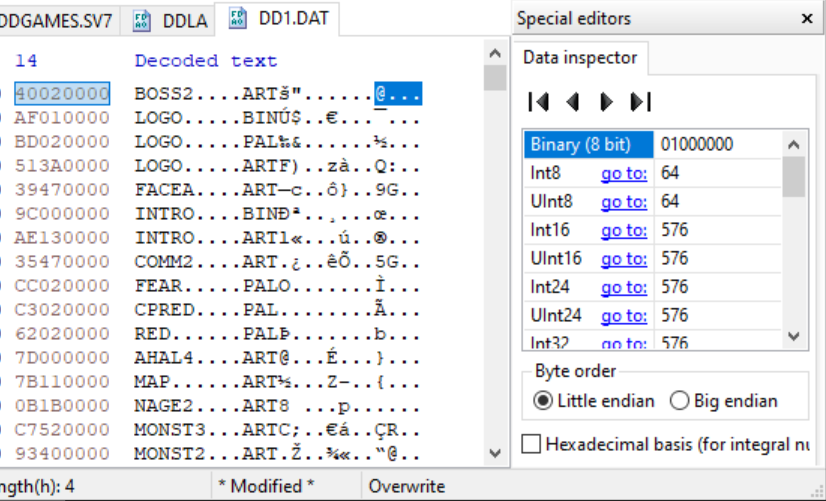

But in this data archive, it’ll be compressed and it will be the length indicated by our last four bytes:

576 bytes.

Knowing that, we can use a tool called QuickBMS to unpack the files from the archive. QuickBMS is a tool that’s designed to do a ton of stuff related to reverse engineering, and one of the things it can do is split up a data file based on commands in a script.

To jump to the chase, I ended up with a script like this:

get file_count short

for file = 1 to file_count

getdstring name 0x08

get null byte

getdstring extension 0x03

String filename P "%name%.%extension%"

get offset long

get uncompressed long

get length long

log filename offset length

next file

Let’s walk through this.

get file_count short

QuickBMS starts at the beginning of the file. Like we learned earlier, the first two bytes (a “short”) are the file_count.

for file = 1 to file_count

…

next file

Looping through the numbers 1 to 369 to get all our files.

getdstring name 0x08

Read the next eight bytes as a string, and store in a variable name. For our first file, this is “BOSS2”. The empty 0x00 bytes will just get dropped like null values.

get null byte

The next byte is the 0x01 flag that tells us the extension is coming. We’ll dump it to a variable we won’t use and just explicitly put a . character into the filename.

getdstring extension 0x03

The next three bytes are always the file extension, so again read it as a string and store it in a variable.

String filename P “%name%.%extension%”

Use a pattern to join together our variables into a filename, BOSS2.ART etc.

get offset long

get uncompressed long

get length long

A “long” is four bytes. So read off the first four bytes as the offset or pointer to where the data is in this file for the filename. Read off the next four as the uncompressed size, which we won’t use in this script, and read off the last four as the number of bytes to read for this file.

log filename offset length

QuickBMS has a “log” api that takes the filename, offset, and length to read data from the archive and write it out to a new file.

If we run this script in QuickBMS, we get 369 game asset files split out from the original archive!

Awesome. And sure enough, BOSS2.ART is 576 bytes:

QuickBMS says that we achieved 100% coverage of the file, so our script split all of the data out and didn’t leave anything behind!

Next up we will see what we can do with these compressed files.